Centeotl (some of the time spelled Cinteotl or Tzinteotl and in some cases called Xochipilli or “Bloom Prince”) was the central Aztec lord of the American corn, known as Maize. The name Centeotl (articulated something like ZIN-TAY-AH-tul) signifies “Maize Cob Lord” or “Dry Ear of the Maize Lord”. Other Aztec divinities related to this immensely significant harvest incorporated the goddesses of sweet corn and Tamales Xilonen (delicate corn), the goddess of seed corn Chicomécotl (seven snakes), and Zippe Totec, the savage lord of ripeness and agribusiness.

Find out more information about different subjects here

Centeotl addresses the Aztec rendition of a more old, Pan-Mesoamerican divinity. Prior Mesoamerican societies, like the Olmec and Maya, loved the Meccan god as one of the main wellsprings of life and richness. Large numbers of the sculptures found at Teotihuacan addressed a maize goddess, with a maize fiber-like ear shape. In numerous Mesoamerican societies, the possibility of majesty was related to the Maize god.

Beginning of Mecca God

Centeotl, Tlazolteotl or Toci, was the child of the goddess of ripeness and labor, and as Xochipilli he was the spouse of Xochiquetzal, the primary lady to conceive an offspring. In the same way as other Aztec gods, the Meccan god had a double perspective, both manly and ladylike. A few Nahua (Aztec language) sources report that the Meccan god was brought into the world of a goddess, and just in later times did a male divinity named Centotl, alongside a female partner, the goddess Chicomécotl, become known. Centeotl and Chicomecoátl noticed various phases of the development and development of maize.

Aztec folklore holds that the god Quetzalcoatl gave Mecca to people. Legend reports that during the fifth Sun, Quetzalcoatl saw a red insect conveying a corn piece. He pursues the insect and arrives where corn develops, the “pile of the plant” in Nahua, or toncatepetl (ton-ah-ka-TEP-eh-tel). There Quetzalcoatl changed himself into a dark subterranean insect and took a piece of corn to return the people once again to plant.

Find out more information regarding the most popular copier company

As per a story gathered by Bernardino de Sahagun, a Franciscan minister, and researcher of the Spanish pilgrim time frame, Centotal made an excursion into the hidden world and got back with a cocktail produced using cotton, yams, houzontle (Chenopodium), and agave, otherwise called octali or pulque. It is said, all that he provided for men. For this restoration story, Centeotl is in some cases related to Venus, the morning star. As per Sahagun, there was a sanctuary committed to Centeotl in the sacrosanct complex of Tenochtitlan.

Mecca God Celebration

The fourth month of the Aztec schedule is called Hui Tzozzatli (“The Big Sleep”) and was devoted to the Meccan divine beings Centotl and Chicomecotl. The month saw different festivals committed to green maize and grass, which started around April 30. To respect the Maize divine beings, individuals made self-penances, performed slaughter customs, and sprinkled blood in their homes. The young ladies embellished themselves with pieces of jewelry of corn seeds. Ears and seeds of maize were brought back from the field, the previous being put before the pictures of the divine beings, while the last option was put away for establishing in the accompanying season.

The clique of Centeotl covered that of Tlaloc and embraced different divinities of sun-based heat, blossoms, devouring, and delight. As the child of the earth goddess Tosi, Sentotle was venerated alongside Chicomecoti and Zilonen during the eleventh month of Ochpaniztli, beginning on 27 September on our schedule. During this month, a lady was forfeited and her skin was utilized to make a cover for the organization of Centrotal.

Mecca God Images

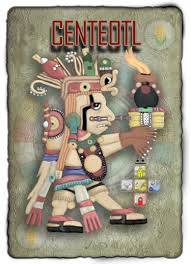

Centeotl is much of the time portrayed in the Aztec codices as a young fellow, with corn bits and ears developing from his head, taking care of staff with green cob ears. In the Florentine Codex, Centeotl is portrayed as the divine force of endlessly gathering creation.

As Xochipilli Centeotl, the god is some of the time addressed as the monkey god Oçomàtli, the divine force of the game, best of luck in dance, diversion, and games. A cut oar formed “palmate” stone in the assortment of the Detroit Institute of Arts (Cavallo 1949) may depict Centrotle getting or taking part in human penance. The god’s head looks like that of a monkey and has a tail; The figure is standing or drifting over the chest of an inclined figure. A huge hit for the greater part of the length of the stone transcends the top of the centotle and is made of maize plants or perhaps agave.